Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church

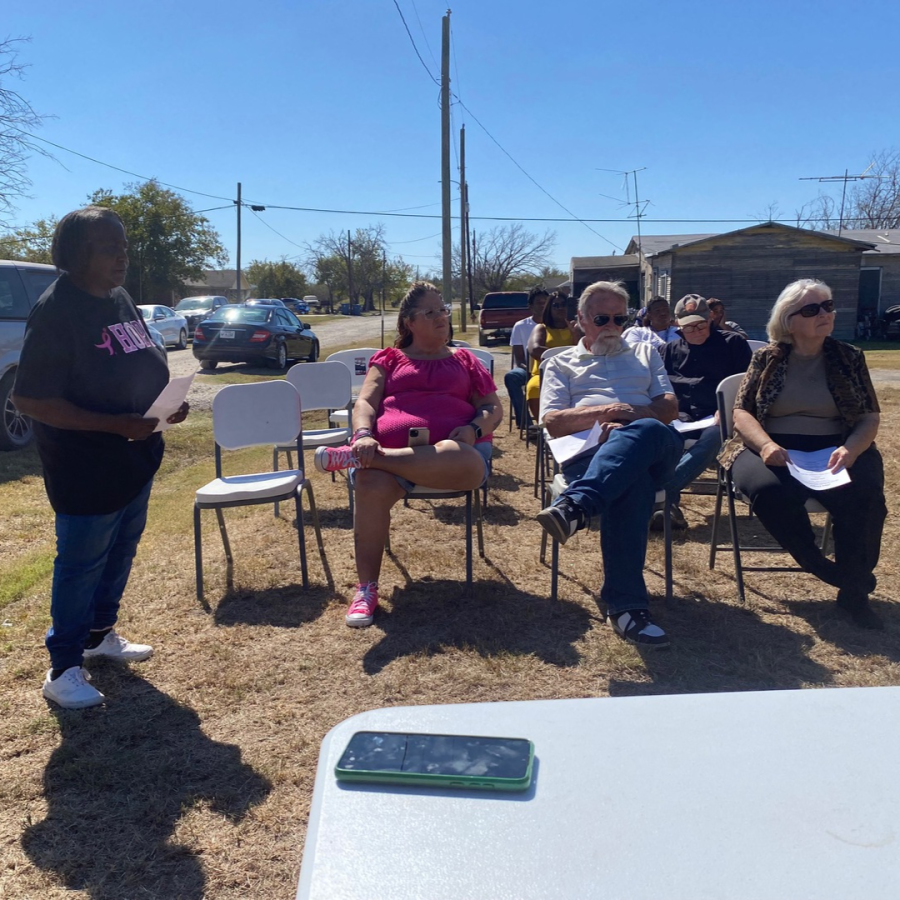

The Texas historical marker for Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Coolidge was dedicated on October 19, 2024. The church was established in 1915. Over the decades, it has served the spiritual, social, and educational needs of the black community in Coolidge.

Narrative History (2018)

ALLEN CHAPEL AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH

I. CONTEXT

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, which had a presence in Texas immediately following the Civil War, took the lead in meeting the spiritual and educational needs of many newly freed slaves. A. M. E. churches were organized in Limestone County at the African-American communities of Comanche Crossing, Sandy, Rocky Crossing and Springfield. As African Americans later settled in other areas of the county, additional churches of the denomination were founded,[1] which included the establishment in 1915 of Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Coolidge.[2]

The town of Coolidge was established by the Trinity & Brazos Valley Railroad in 1903 with the city government being incorporated on April 19, 1905.[3] By 1910 the community had a population of 500 and by 1914 had two banks, a weekly newspaper, and several businesses. During the early 1930s the population reached 1,169 but began to decline after the railroad decided to abandon the rail line through the town in 1942. [4] The U. S. Census Bureau estimates the population of the town in 2017 as 957.[5]

Like most of the communities in Texas at the time, Coolidge was segregated both socially and geographically. African Americans lived in a section of the town known as “The Flats” and had to establish separate churches, a separate cemetery, and a separate school from those of the White citizens. At least four African American churches were established early in the history of Coolidge of which two, the Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church and the St. James Primitive Baptist Church, are still in existence. Throughout its history of over 100 years, the Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church has played a vital role in helping to meet the spiritual, physical, educational, and social needs of the African American community of Coolidge.

II. OVERVIEW

Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church is named in honor of Bishop Richard Allen. Richard Allen was born the slave of Benjamin Chew in Philadelphia in 1760. Around 1768, his parents, his three siblings, and he were sold to a plantation owner in Delaware named Stokely Sturgis. With the permission of his owner, Allen began to attend Methodist meetings and converted to Methodism in 1777. In 1780, Sturgis agreed to let Allen hire himself out in order to earn money to purchase his freedom for $2000. In addition to performing manual labor, Allen began preaching at Methodist churches in Delaware and neighboring states. In 1786, Allen paid the last installment to Sturgis to gain his freedom. Later that year, he accepted an invitation to preach at St. George’s Church in Philadelphia, a mixed-race congregation of Methodists.[6]

After Allen’s arrival, African American membership increased considerably to the point that the building could no longer accommodate the growing congregation. Rejecting Allen’s request to provide a separate place of worship for the African American members, the White elders of the church decided to install a balcony in the church to provide separate seating for African American worshippers. In 1787, Allen and Rev. Absalom Jones founded the Free African Society, a nondenominational religious association and mutual aid organization, but Allen left the organization after two years. One Sunday morning in 1792, Rev. Jones challenged the segregated seating policy at St. George by sitting downstairs. In the middle of the opening prayer, two white trustees forced Jones to leave. Allen and other African American members who had been seated in the balcony walked out. Until this incident, few African American Methodists had been receptive to Allen’s call for the establishment of a separate church. On August 12, 1794, the Free African Society founded The African Church of Philadelphia, which was consecrated as part of the Protestant Episcopal Church because of the Methodists discriminatory treatment of the African Americans. Rev. Jones became the denomination’s first African American priest. Allen was still committed to Methodism and used his own savings to purchase an old blacksmith shop, which was moved to a new location and renovated. Bethel African Church opened on April 9, 1794, and Allen was ordained as its deacon. After Bethel was officially initiated at the 1796 Methodist conference, White Methodist officials attempted to gain control over Allen’s church, but a Pennsylvania Supreme court ruling in 1807 declared that the African American congregation owned the property on which they worshipped and that they could determine who would preach there. Following Allen’s example, many African American Methodists formed their own churches in northeastern cities. Allen organized a conference for African American Methodists in 1816 to address their shared problems. The leaders decided to unite their churches under the name of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This allowed them to gain control over the governance of their churches and placed them beyond White ecclesiastical jurisdiction. Conference attendants elected Allen the first Bishop of the new denomination, a position he held until his death in 1831. After his death, the A. M. E. Church continued to spread throughout the Western and Northeastern United States, especially in Indiana, New York, Washington D. C., and Massachusetts.[7]

During the Civil War, A. M. E. missionaries, sometimes serving as chaplains, followed Union troops into the collapsing Confederacy to evangelize the newly freed slaves and to provide them with assistance with their social and educational needs. “I Seek My Brethren” was the title of an often-repeated sermon that Theophilus Gould Steward, A. M. E. minister, preached in South Carolina that became the clarion call to evangelize fellow African Americans in Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Texas, and many other parts of the South.[8]

The first A. M. E. missionary in Texas, M. M. Clark, arrived in Galveston in 1866. Many African American Methodists had previously worshipped in the churches of their masters, and Clark worked to bring them into the A. M. E. Church and to convert others to Methodism. The first Texas conference met in Galveston on October 22, 1868, which claimed 3,000 members. Membership in Texas reached 23,000 by 1890, and 34,000 by 1926.[9] The Texas Conference founded the Connectional High School and Institute in Austin in 1872 with the original purpose to educate freed slaves and their children. After moving to Waco in 1877, the name was changed to Waco College and the focus changed to proving vocational education in the areas of blacksmithing, carpentry, tanning and saddle work. Later, the curriculum was expanded and the school was chartered by the State of Texas in 1881 with the name Paul Quinn College. The school moved to Dallas in 1990.[10]

A. M. E. churches were organized in Limestone County at the African-American communities of Comanche Crossing, Sandy, Rocky Crossing and Springfield. As African Americans later settled in other areas of the county, additional churches of the denomination were founded.[11] Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church was established in Coolidge in 1915. Original trustees of the church were J. W. Wilson, A. Davies, H. L. Lonzo, M. T. Tatum, J. H. Lynn, B. J. Anderson, J. Jones, and J. Whitaker.[12] According to current members, who assume that most of the early members had no formal education, early church records were not kept. The church was organized in the home of one of the original trustees, and during the first few years, the congregation met in individual members’ homes for worship. Financially poor but determined to make a change and by applying spiritual prayers and work, members saved pennies and nickels to construct a church building in 1918, which is still located at 105 Parker Street.[13] According to Earline Driver, a 98 year-old resident of Coolidge, there were about 25 church members during the 1930s.[14]

Some of the pastors who have served Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church have been Rev. Doo Winn, Rev. G. P. Smith (1947), Rev. Will Davis (1948), Rev. Martin Trammel (1958-1962), Rev. Carl Tatum, Rev. L. W. Parker (1962-1964), Rev. W. B. Williams (1965-1966), Rev. G. W. Grey (1966), Rev. J. H. Hill (1974), Rev. Donald Shaw (1975) Rev. Stanley Johnson (1982-1992), Rev. Mary Wadley (1992), Rev. T. J. Miles (1993), Rev. Rainbolt, Rev. Georgia Rundless, Rev. Horace Hill, and Rev. Myra Turner Billips (1998-2003). Rev. Alfreda Henderson is the current pastor, serving in that capacity since 2003.[15]

Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church has been very active in serving the African American community of Coolidge. From its earliest times through the late 1960s, “mission work” was conducted every Wednesday afternoon with members of the church visiting homes in “The Flats” to minister to the spiritual and physical needs of each household. For example, if the mother of a home was ill, then church members would clean the house, wash clothes, and cook meals for the family in addition to offering prayers and words of encouragement.[16] For many years, the church hosted a program at the close of each school year. The church building has also served as a meeting place for many community organizations. On several occasions, the church hosted home demonstration programs that were offered by the county extension office.[17]

Two events during the 1960s left a lasting imprint upon the congregation. On September 21, 1960, Coolidge City Marshal Arthur S. Todd was fatally shot while attempting to arrest an African American driver for reckless driving. [18] Fear swept across “The Flats” as people living there feared retaliation from the White community. Members of Allen Chapel and other African American churches prayed for Todd’s family and for peace and calm in the community.[19] On January 20, 1968, one of the church’s members, William Steven Calhoun, paid the ultimate sacrifice when he was killed in Vietnam at the age of 23. The church has recognized him as “Our Hero.”[20]

Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church currently has 30 members who continue the tradition of serving the community. Works of the church include giving scholarships to local college students, volunteering at Caritas, helping clean the Brown-McGee Cemetery (the African American cemetery in Coolidge), hosting meetings of the NAACP, giving fruit baskets to members of the community during the holidays, collecting backpacks and school supplies for local students, paying for attendance to church school conferences, and regularly visiting local nursing homes.[21] The congregation recently acquired property with three buildings at 305 Bell Street. One building will be used as the church sanctuary, one as a fellowship hall, and the third as a maintenance/utility building. Members are looking forward to worshipping in their new home and the prospects of increased opportunities to serve and minister to the community.

III. SIGNIFICANCE

Founded in 1915, the Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Coolidge has been a vital part of the community for over 100 years. Through local mission work, the congregation has ministered to individuals and families in need. The church has also hosted numerous religious, educational, and social events that have had a positive impact on the community.

IV. Documentation

[1] Cotton, Walter, History of Negroes in Limestone County. Mexia, Texas: Dr. J. A. Chatman & S. M. Merriwether, circa 1940. pp. 27-28.

[2] Cornerstone of Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church located at 105 Parker Street, Coolidge, Texas.

[3] Walter, Ray A., A History of Limestone County. Austin: Von Boeckmann-Jones, 1959. p. 114.

[4] Handbook of Texas Online, Vivian Elizabeth Smyrl, "COOLIDGE, TX," accessed November 02, 2018, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/hlc49.

[5] U. S. Census Bureau

[6] Founder’s Day Brochure, Richard Allen, Tenth Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, February 2012.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Handbook of Texas Online, William E. Montgomery, "AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH," accessed November 05, 2018, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ima02.

[10] Handbook of Texas Online, Douglas Hales, "PAUL QUINN COLLEGE," accessed November 05, 2018,http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/kbp08.

[11] Cotton, Walter, History of Negroes in Limestone County. Mexia, Texas: Dr. J. A. Chatman & S. M. Merriwether, circa 1940. pp. 27-28.

[12] Cornerstone of Allen Chapel A. M. E. Church located at 105 Parker Street, Coolidge, Texas.

[13] Interview with Alfreda Henderson by William F. Reagan, November 3, 2018. (notes in the possession of William Reagan: wfreagan@embarqmail.com)

[14] Interview with Earline Driver by Alfreda Henderson, October 24, 2018. (notes in the possession of Alfreda Henderson: ahenderson377@yahoo.com)

[15] Alfreda Henderson interview

[16] Ibid.

[17] Alfreda Henderson interview

[18] Officer Down Memorial Page, “City Marshal Arthur S. Todd,” accessed November 5, 2018, http://www.odmp.org/officer/16841-city-marshal-arthur-s-todd.

[19] Earline Drive Interview

[20] Obituary of PFC William S. Calhoun