Limestone County Heritage Symposium 2019

Trinity University

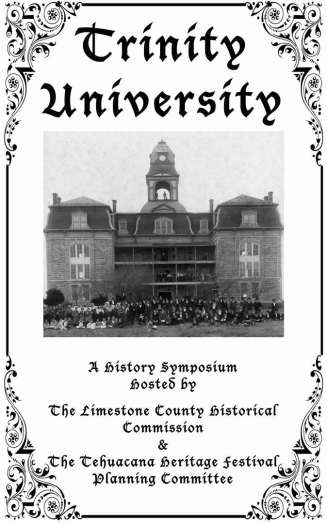

The Limestone CHC and the Tehuacana Heritage Committee sponsored a history symposium as part of the 150th anniversary celebration of the establishment of Trinity University in Tehuacana, Limestone County in 1869. The university later relocated to Waxahachie in 1902 and then to its current location in San Antonio in 1942. The Tehuacana Art Institute hosted the event in Texas Hall on the old Trinity University campus. Trinity University made their archives available for research and provided period costumes from their theater department. The chair of the university’s history department, Dr. Carey Latimore, delivered a keynote address. In addition to Dr. Latimore’s speech, the symposium featured local reenactors who portrayed early faculty members and John Boyd who donated the land for the university. State representative Kyle Kacal also delivered a speech and made a special proclamation.

State Representative Kyle Kacal Makes Proclamation

Trinity University Historical Facts

Historical Narrations by Tehucana Community Members

Keynote Address by Dr. Carey Latimore

Dr. Carey Latimore, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of History at Trinity University in San Antonio where he is the Chair of the History Department. He holds a M.A. and Ph.D. in United States History from Emory University and a B.A. from the University of Richmond.

Dr. Latimore has received numerous awards and recognitions. He is also a member of Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, Phi Theta Kappa National Honor Society, the Golden Key National Honor Society, and the Phi Alpha Theta History Honor Society.

An ordained minister, he is the author of two books and is currently working on a new book, “Stories of Faith and Inspiration: African Americans’ Journey to Canaan,” scheduled to be released in 2021.

Proclamations & Presentation

Why Tehuacana?

by Rose Mary Magrill

Presbyterial Historian for Trinity Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

An educator of the 21st century might well wonder: “What were they thinking—those members of the site selection committee for Trinity University—when they selected Tehuacana over Dallas as the best place to found what they hoped would be a major institution?” The answer, of course, is that they were thinking like men of the mid-19th century. First, colleges should be situated in healthy locations –high enough in elevation to avoid swampy rivers and all the diseases associated with them and with plenty of fresh water easily available. Second, young men would be more studious if they were kept away from the vices and distractions of the large towns, therefore small, fairly-isolated communities were the best locations for colleges. Tehuacana Hills met those two site selection criteria without any difficulty. An 1888 history of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church noted “there was then no town in Tehuacana” when Trinity was established and went on to conclude: “Health, morality, and freedom from temptations ought to weigh more than all the advantages afforded by a large city.”1

There was one requirement for locating a new college on which modern educators and those of 150 years ago could easily agree. Who will offer us the most money? In fact, the site selection committee for Trinity University determined at the beginning that they must be offered no less than $25,000 by the place that wanted to secure the university. Dallas, Waxahachie, and Round Rock all placed bids that met the minimum requirements, and the folks from Dallas lobbied the selection committee vigorously to choose that city. Thanks to John Boyd, Tehuacana met the money requirement and—according to some estimates at the time—exceeded it. The offer of a town site of 130 acres on a hill and fifteen hundred acres of land on the prairie below, as well as a building that could temporarily house the new school, made the selection of Tehuacana an easily-defended decision (at the time). Texas was still enduring Reconstruction in 1869. Many people had more land than money, but it was hard to know what that land might be worth until it was actually sold. As a Cumberland Presbyterian historian noted, the lands at Tehuacana were “estimated then at figures far beyond what was found afterward to be their value.” 2

Cumberland Presbyterians—many of whom hurried to Texas for the cheap land as soon as it was opened to Anglo settlers—wanted educational opportunities for their children. Delegates to the first meeting of Texas Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in San Augustine County, Republic of Texas, in November 1837, passed a proposal “for the establishment of a seminary of learning, as soon as possible.” “As soon as possible” did not mean immediately in 1837. That this was an “unsettled frontier” is illustrated by the fact that one elder who was planning to attend that November meeting missed it because he was killed by hostile Indians on his way there. The second meeting of Texas Presbytery, in September 1838, had to be moved because the designated meeting place had “been entirely broken up by hostile Indians.” 3

In spite of hardships, the number of congregations and ministers grew rapidly and by 1854 Cumberland Presbyterians in Texas were organized into three synods, each of which contained three or more presbyteries. By the time of the Civil War, each synod had a state-chartered collegiate institution within its bounds. Texas Synod, the northernmost unit of the church, had Chapel Hill College, located in Daingerfield, described by the promoters of the college as “a pleasant, healthy and romantic village, ... and on account of its remoteness from anything calculated to … draw off the mind from study, … it is a delightful location for a literary institution.” (In 1846, it had been described by a traveler through the area as consisting of “three or four cabins scare fit for pigsties.” Even so, three years later with a post office and a few more cabins, it was considered an appropriate place for a college.) Chapel Hill College received free land in 1849 at Daingerfield, was chartered by the state of Texas in 1850, and opened for classes in February 1852. William E. Beeson was the first president of Chapel Hill College and Samuel T. Anderson was one of the early faculty members. (Both later served Trinity University.) 4

Colorado Synod, the southernmost judicatory, was served by Ewing College in LaGrange. This institution had offered instruction for several years before it was chartered as La Grange Collegiate Institute in November 1850. The charter was revised in February 1852, when the name was changed to Ewing College. Brazos Synod was geographically the central unit of the church. Its own antebellum college grew from Larissa Academy, which opened for instruction in Cherokee County by at least 1848. The academy received a state charter as Larissa College in 1856. This school was in such a rural location that only an expert in Cherokee County history can find the site today.5

All three of these colleges were established in areas where large numbers of Cumberland Presbyterians had settled early and all three enjoyed some periods of prosperity before the Civil War. They are important in the founding of Trinity University, because the three synods had to agree to cut loose these colleges that they had supported for years in order to pool their resources for the founding of Trinity. Each college ended up contributing something. Colorado Synod sold the buildings of Ewing College and gave the money to Trinity. Larissa College, which had—for its time—a “splendid set of chemical, philosophical, mathematical, and meteorological instruments” as well as “quite a collection of geological and mineralogical specimens” and a large, expensive telescope, sent those pieces of equipment to Trinity. Chapel Hill College was returned to the ownership of Marshall Presbytery, which had originally established it, and Chapel Hill continued to exist for a number of years. Although it did not supply money or equipment, Chapel Hill furnished Trinity its first president, William E. Beeson.6

The beginning of the Civil War totally disrupted colleges in Texas, as young men and their professors rushed off to enlist. After the War, it was difficult for some of these schools to revert back to their collegiate status. There were fewer young men who had the time to devote to full-time study and those who had formerly provided the financial support had no money. New ideas were needed if higher education was to be revived in Texas. The first discussions of a university supported by all three synods are reported to have begun within Brazos Synod. In 1866-67 the three synods elected delegates to a joint educational committee, which met in Dallas in December 1867, to consider what might be done to establish “an institution of learning of high order within their bounds.” The committee members reported to their respective synods that such an establishment was a good idea and they should proceed promptly to select a location.7

The joint site selection committee of the three synods duly visited the four sites that offered appropriate donations to become the home of Trinity University and at a meeting in Waco in April 1869 unanimously selected Tehuacana as the location. The committee members made plans to secure a charter from the state, elect trustees, and select a faculty so that classes could begin in the fall. Davis M. Prendergast, a lawyer from Mexia and one of the first trustees, secured the state charter in August 1870. (At the same time, Prendergast managed to get a law enacted that outlawed the sale of liquor or the operation of any gambling equipment within two miles of Trinity University. Fines could run as high as $100 per offense.) The new university charter provided for nine trustees, with each synod nominating three trustees; but all of the trustees had to live within twelve miles of Tehuacana. The committee’s first choice for president of Trinity University (Dr. Thomas B. Wilson of Marshall, Texas) did not accept; so William E. Beeson, from Chapel Hill College, was elected.8

Having taken a daring step by merging the educational efforts of the three synods, committee members made another innovative move by naming the new institution “Trinity”—because of “the joint work of the three synods, in the name of the Holy Trinity.” Choosing to name the school “University” instead of “College” indicated their high aspirations—more than the reality of the situation. Classes began at the new Trinity University on September 23, 1869, in the Boyd house that had been given to the school. Although it took almost the entire first semester for them to arrive, approximately one hundred students eventually made their way to Tehuacana in that first year.9

The old Boyd home was certainly not intended as a permanent classroom building, but the trustees had trouble collecting enough money for the first building. The first wing of what was intended to be the main building was started in 1871. Several accounts say the foundation was laid off in the form of a capital “T” for “Tehuacana” and “Trinity,” but the first wing was only the stem of the “T.” Construction was slow, and classes were finally held there the fall of 1873. The additional wings planned for the main building were started in 1886, with the north wing being completed in 1887. The south wing, a mansard roof, and a cupola completed the building in 1892. McDonnold, who was writing his history of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church at the time the Trinity buildings were going up, described the first phase of the building (the stem of the “T”) as “utterly destitute of any architectural pretensions;” but he did go on to say that the second phase of the building then under construction was “said to be a fine structure.”10

Trinity University experienced many problems while it was located in Tehuacana. Financial problems existed from the opening of classes to the departure of the university to Waxahachie. Often fundraising efforts were impacted by other problems, such as the disagreement about co-education. The charter of Trinity University provided that the institution would admit both men and women. The problem, in the eyes of some people, was not that both men and women attended the same institution, but that they sat in the same classrooms. At first, necessity required that they be taught together, because the Boyd house was not spacious enough to allow for instruction in different classrooms. After the first wing of the main building was occupied in 1873, the Boyd house, which the trustees had at one time designated as the headquarters for the female department, seemed to be available for that purpose. However, the faculty and most of the trustees thought the preparatory department should be put there, and the new building used for coeducational classes—as the old building had been. The Board of Trustees, with a vote of two against, agreed to that arrangement. The two trustees who opposed the plan tried to convince the three sponsoring synods to “remove the evil” of coeducation. This was discussed at length in the 1872-73 meetings of the synods, but the faculty’s arguments in favor of co-education eventually prevailed. The faculty statement to the synods emphasized that coeducation was by then practiced by some of the country’s leading universities, that other Cumberland Presbyterian institutions had successfully adopted coeducation, and that it was financially impossible to maintain two separate faculties in order to staff a female department. Financial considerations usually prevail and they did in this case. The men and the women continued to attend the same classes.11

Another controversy arose about the same time that greatly affected the university. The exact cause of the problem is difficult to determine, but there was evidently great dissension among the members of the Literary Department and President Beeson. Brackenridge notes in his history of Trinity that official records offered few clues about this problem and denominational and regional newspapers provided no information. Campbell and McDonnold do not even mention the existence of a problem, although Campbell does note that Beeson resigned as president in 1877. Both Brackenridge and Campbell imply that it was during the planning for a separate theological department, established in 1878, that the unknown problem festered. The trustees tried to solve the problem by making adjustments in university governance—giving the faculty more control and adjusting the requirements for trustees. Their last desperate measure was to ask for the resignations of Beeson and the other three instructors in the Literary Department—only one of whom had not been at Trinity since the beginning.12

During this time, rumors were moving throughout the entire denomination about the situation (whatever it was) at Trinity, and the trustees were beginning to worry very seriously about the future of the institution. When one looks at the history of the denomination more broadly, as well as at the history of Trinity, the suspicion arises that the relative newcomer on the faculty, Thomas M. Goodknight, might have had a hand in this disturbance. Born in Kentucky and still there at the time of the 1870 census, Goodknight arrived in Texas by at least the fall of 1874, when he was received into a presbytery in the Austin area. He made a good impression on the Trinity trustees, because he was the first fired faculty member they tried to rehire. Who knows what Goodknight was advocating while he was on the Trinity faculty, but by the fall of 1878 he and four other ministers in the area around Tehuacana were publishing ideas that “viewed from any stand-point are surely extraordinary.”13

Goodknight was one of several ministers from Limestone and Navarro counties who left the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in early 1879—and were formally deposed by their presbyteries—for their promotion of sanctification. They had established something called the Temple of the Coming Lord in Corsicana and published pamphlets on their visions and healings. Members of Texas Synod were having none of this kind of heretical doctrine in their midst. “We as a Synod,” they proclaimed in 1879, “heartily detest the doctrines as held and taught by such fanatics.” The layperson’s view was expressed a few years later, in reference to one of Goodknight’s colleagues in heresy, Robert J. Haynes: “It is passing strange that the brains of persons otherwise noted for soundness, will become diseased, and filled with vagaries that would probably provoke laughter were it not for their solemnity.”14

The final problem—and the decisive one—that ended Trinity University’s time in Tehuacana was the changing views about the appropriate location for institutions of higher learning. By the end of the 19th century, educators were more interested in increasing enrollment than in protecting their students from the vices of the big cities. Educational institutions needed to be accessible to large numbers of prospective students; and Tehuacana, which recorded a population of 382 in the 1900 census, was no longer an inviting location.

Two sudden deaths in the Trinity leadership appeared to accelerate the departure of Trinity for Waxahachie. President Beeson, who had been rehired by the trustees in 1878, died suddenly of complications of a stroke in September 1882. This event was later seen as marking the beginning of the end of Trinity’s sojourn in Tehuacana. Those who wanted to relocate the university to an urban setting became more vocal. This caused others who might have donated money for buildings and endowments to hesitate about sending their gifts to a place soon to be vacated. The president who followed Beeson lasted until September 1885. Only two months after he arrived in Tehuacana to head the preparatory department, Luther A. Johnson was appointed by the trustees in 1885 to be president of the university. He served in that position for less than ten years total, but Johnson was a widely-respected leader at Trinity. Until his sudden death from typhoid fever in July 1900, he was one of the strongest and most effective proponents of keeping Trinity in Tehuacana. Following Johnson’s death, those in favor of moving the university renewed their efforts.15

By 1889 all of the synods of Texas had merged back into one Texas Synod, which meant that decisions about Trinity University only needed the approval of one synod. At the meeting of Texas Synod in the fall of 1900, memorials were received from five presbyteries asking that action be taken to remove Trinity University from Tehuacana and transfer it to a larger town or city. The committee of synod that considered these requests agreed that removal was a good idea and recommended that a committee of seven should be appointed to see which town would offer the best deal, financially speaking. Robert M. Love, representing Tehuacana Presbytery, filed a minority report asking synod to affirm that “Trinity University is properly and judiciously located” in Tehuacana. Forty-five of the 97 voting delegates supported Robert Love’s minority report. [Personal note: my great, great uncle, a delegate from Marshall Presbytery, was one of those voting with Robert Love to keep Trinity in Tehuacana.] In the final vote, fifty-three delegates supported the majority report that recommended moving the university as quickly as an acceptable town made a good offer. The citizens of Waxahachie, with a population in the 1900 census of 4,215, quickly assembled the most attractive offer and the deed was done. (Classes opened in Waxahachie on October 9, 1902.)16

Trinity University moved away but it left many reminders of its existence in Tehuacana. After the decision was made to move the university to Waxahachie, opponents of the move threatened to file for an injunction. To avoid the time and trouble of a lawsuit, Texas synod through its commissioners offered to give all the university’s buildings and land holdings to the town of Tehuacana.

The Tehuacana Cemetery is filled with the remains of people who were important in Trinity University’s early history. This includes two presidents, William E. Beeson and Luther A. Johnson, and the father of another president (Samuel M. Hornbeak, the father of Samuel L. Hornbeak, who served after the move to Waxahachie.) Of the five original faculty members, four are buried at Tehuacana: William Beeson and his wife Margaret, who taught music; W.P. Gillespie and his wife Kate, who also taught music. David A. Quaite, who joined the faculty in 1870 and died in 1873, is also buried there, as is his wife who survived him by 66 years.17

Trustees of the university are buried in Tehuacana. T.W. Wade, who served as treasurer of the Board of Trustees from the time he moved to town in 1872 until his death in 1895, is said to have kept “all the endowment notes and valuable papers in a small hand grip which never left his sight during the day, and at night it was under his bed, to be the first thing cared for in case of fire.” John W. Pearson had a full range of connections with Trinity. First, he was a student; then he served as the financial agent (equivalent to today’s development officer), and later he was elected a trustee. He strongly opposed the move to Waxahachie.18

Numerous supporters of Trinity rest in the local cemetery. Most prominent are the graves of John Boyd, who first enticed the university to Tehuacana, and Robert M. Love, who tried so hard to keep it in Tehuacana. A.S. Watkins, another supporter, was part of the family that donated Watkins Hall to house ministerial students enrolled at Trinity. The cemetery also contains Cumberland Presbyterian ministers who may not have been directly connected to Trinity, but were nevertheless important in church history. Among them are Robert Donnell King, a descendant of one of the three ministers who founded the first Cumberland Presbytery in Tennessee in 1810; Daniel G. Molloy, a pioneer minister who served the area around Tehuacana and also taught at Tehuacana Academy (an antebellum preparatory school that did not survive the Civil War); and Reuben E. Sanders, who served a preaching circuit in Limestone County in 1848. Tradition says he was the first person to identify Tehuacana Hills as a promising site for a college.19

Notes

1 B.W. McDonnold, History of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church (Nashville, TN: Board of Publication of Cumberland Presbyterian Church, 1888), p. 552.

2 R. Douglas Brackenridge, Trinity University; A Tale of Three Cities (San Antonio, TX: Trinity University Press, 2004), p. 13; Thomas H. Campbell, History of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Texas (Nashville, TN: Cumberland Presbyterian Publishing House, 1936), p. 98; McDonnold, p. 552 (quote).

3 Minutes of Texas Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, October 1837 and September 1838; Campbell, pp. 29-31.

4 Rose Mary Magrill, “Higher Education on the Frontier: Chapel Hill College in Daingerfield, Texas,” East Texas Historical Journal, 43 (1):9-67, 2005.

5 Johanna Caroline Walling, “Early Education in Fayette County” (Unpublished M.Ed. Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1941), Appendix; Nellie Jean Evans, “A History of Larissa College” (Unpublished M.A. Thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1941), p. 35-38.

6 Campbell, pp. 92-96.

7 Minutes of Brazos Synod of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, October 1866; Minutes of Colorado Synod of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, October 1867; Minutes of Texas Synod of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, pp. 244-245.

8 Brackenridge, pp. 16-18; Campbell, pp. 97-101.

9 Brackenridge, pp. 18-21.

10 Brackenridge, pp. 28; 64; Campbell, pp. 102-103; McDonnold, p. 533.

11 Brackenridge, pp. 28-31; Minutes of Brazos Synod … , October 1873; Minutes of Colorado Synod … , October 1873; Minutes of Texas Synod … , pp. 106-107; p. 115.

12 Brackenridge, pp. 31-33; Campbell, pp. 103-104.

13 Brackenridge, pp. 31-33; Campbell, 103-104; Minutes of Brazos Synod …, p. 105.

14 Texas Presbyterian, Mar. 21, 1879; Minutes of Texas Synod …, p. 242; Longview (TX) Democrat, Feb. 8, 1884.

15 Brackenridge, pp. 42-46; 64-65.

16 Minutes of Texas Synod …. 1900, pp. 18-23.

17 Brackenridge, p. 21.

18 Campbell, p. 101 (quote).

19 D.S. Bodenhamer, “Trinity University Commencement,” The Cumberland Presbyterian, January 13, 1895 (tradition concerning Sanders).